What happens when two universities decide to become one?

QS MidWeek Brief - October 29, 2025. How do you merge universities? We speak to someone who has helped do just that. And how should we live our lives?

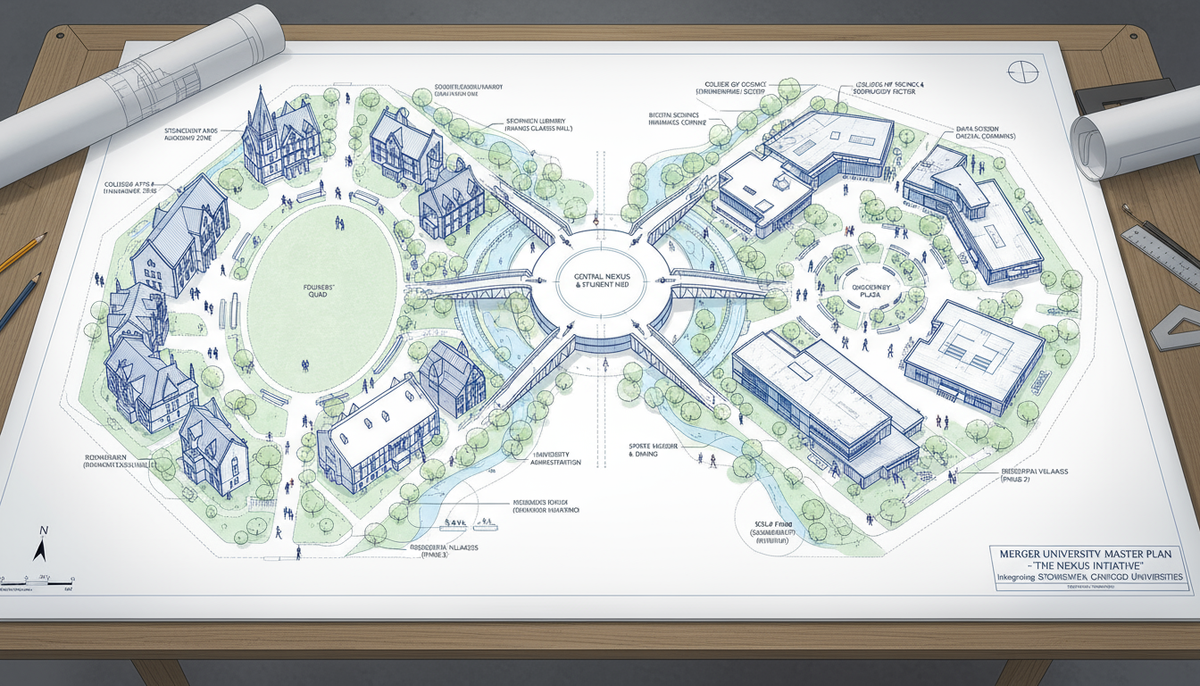

Welcome! Last week, we looked a little at the history and why of university mergers. This week, we’re looking at the how, in a one-on-one interview with someone who worked on doing just that. At the start of next year, Adelaide University will officially open, but the process of getting there is fascinating.

Mergers can come out of existential questions. This week, we have a poignant guest essay which asks us “How should we live our lives?” I, personally, think we should live out lives connected, and you can make new connections next week in Seoul at the QS Higher Ed Summit: Asia Pacific. Limited tickets available.

Stay insightful,

Anton John Crace

Editor-in-Chief, QS Insights Magazine

QS Quacquarelli Symonds

How to Design a University

By Chloë Lane

It wasn’t until she worked as an au pair in Germany that Adelaide University’s new Deputy Vice Chancellor for International and External Engagement, Professor Jessica Gallagher, discovered her spark for education.

“I didn’t think university was for me,” she admits. “Of course, my family find that hilarious now,” she adds with a smile.

Born in Queensland, Australia but growing up in both Vancouver, Canada alongside her four siblings, Professor Gallagher is well seasoned to adapting to a change in location. As a child she attended five primary schools and two high schools. When she finally moved back to Queensland in her teens, the University of Queensland seemed like a good fit. But the reality was a major culture shock.

“I just wasn't sure it was the right fit for me,” she says. “It was then that I decided to go and work and study overseas.”

Her father was a high school principal, so Professor Gallagher and her siblings grew up with an interest and curiosity around learning.

She is a self-confessed “history buff”, fascinated with the history of World War II, the division of Germany, the fall of the Berlin wall and the challenges that then ensued. Germany, then, held a special appeal for Professor Gallagher at that time. She’d studied the language and was keen to improve her language skills.

“I thought I would just go and work for six months and then go backpacking,” she admits. But as she went over to Germany to do just that, she realised how much she loved the country and made the bold decision to enrol in a study abroad programme, not a typical move at the time.

The Importance of Education

Professor Gallagher enrolled as a continuing student at Justus Liebig University Giessen: just 40 minutes from Frankfurt. There were many international students, and she built global connections, gaining a stronger understanding of German language, culture and European history. “I absolutely loved it,” she says. “I always thought I’d end up living and working in Germany.”

But she made her way back to Australia to finish her final year, spending all her semester breaks travelling back and forth from Germany. Afterwards, she was offered the opportunity to study in Freiburg on a German Academic exchange programme. Then, years later when completing her PhD, she was a visiting research scholar at the Free University of Berlin.

“It completely changed my life,” she states. “It has an amazing diversity of people and perspectives and such a rich history. I think it was a big part of why I’m in the role I’m in now. [Studying abroad] certainly shaped my view around the importance of education.”

A Merging of Cultures

It's this merging of cultures that Professor Gallagher particularly enjoys, and an environment she thrives in, and is a trait she brings to her role of Deputy Vice Chancellor for International and External Engagement at Adelaide University, which officially opens its doors in January 2026.

A merger of the University of Adelaide and the University of South Australia, Adelaide University will mix the old with the new; the former is 151 years old, while the latter is just 33.

“There is so much complexity around every decision because of the interdependencies and the expectations of stakeholders, and knowing that there's a responsibility to get this right,” she says. “It’s incredibly inspiring, I’ve learnt so much.”

Both universities have very clear strengths and legacies, and now they’re coming together to create something new. If you look at other mergers, Professor Gallagher explains, you’ll see that they often put an umbrella over the top, but the entities remain. “Whereas this really is the merger of two equals. When people see what we’ve done they’ll see a genuine commitment to co-creation.”

Three thousand academics were brought together alongside hundreds of industry partners to ensure the programmes Adelaide University are offering are fit for purpose. In a sometimes slow-changing industry, it’s not something universities usually get the opportunity to do, Professor Gallagher notes.

It’s not lost on the rest of the industry either. “We've had so many visits from global institutions that are really interested in the change process,” she says. “I think we’ve generated some interesting learning points on how to develop and deliver a project of this nature that could be informative for other groups that decide to go down this path.”

Shaping the future

“Being the eyes and ears of the organisation” is how Professor Gallagher describes her new role. She sees engagement as a core part, strengthening connections with industry, government, global partners, alumni, and partnering with the community where it matters.

Professor Gallagher’s role is extremely broad, and she’ll draw on her extensive experience as Pro Vice Chancellor at the University of Queensland and Deputy Vice Chancellor at the University of Adelaide.

She hopes to gain a greater understanding of market trends, social pressures, sector needs and opportunities and then work with colleagues to address these, whether that’s through research or building programmes and initiatives.

“We have ambitions to be Australia’s most connected university,” Professor Gallagher reveals. “Those connections to tell those stories and to create those partnering opportunities because they really, really matter, and they enable us to really extend our impact.”

Whether that’s building new partnerships in Vietnam, or working with small and medium enterprises, connectedness presents opportunities for faculty and students as well as the wider community.

Chloë Lane is a gold-standard NCTJ-trained journalist specialising in higher education. A former Content Editor for QS, Chloë has a wide range of experience writing articles for a variety of B2B and B2C publications about topics related to business schools, universities, careers and academic research.

How Should We Live Our Lives?

By Professor Dawn Freshwater, Vice-Chancellor, Waipapa Taumata Rau, University of Auckland

The question of how we should live our lives is not simply a navel-gazing question about the nature of being and existence. Many of us would argue that it is a question now in sharp relief, given the overlapping crises facing humanity. It is also a question of what humanity is, how it has changed and how we will know ourselves in the future. It is, essentially, as much about what knowledge is and how we understand it, as about who will control it. One might say this fundamental question has never been more urgent.

The ongoing undermining of arts, humanities and social sciences education, along with the loss and defence of associated research funding, has itself become the subject of much recent writing. Yet, the issue reaches beyond money. This significant area of scholarship reflects what societies value and what they are prepared to let wither.

That mirror reveals a worrying global divide. Across much of the West, the arts, humanities and social sciences (AHSS) are being cut back, sidelined or forced into narrow, utilitarian roles. In Asia, by contrast, governments are treating these disciplines as strategic assets. They are investing in them to build identity, cohesion and global influence. If universities, policymakers and decision-makers in Western democracies do not act, they risk not only ceding cultural and intellectual leadership for a generation, but also losing the chance to connect new technologies such as AI with real human experience.

The evidence of such retrenchment is stark. Governments are choosing to “deprioritise” AHSS research by reducing or cancelling research funding. In New Zealand, the humanities and social sciences are no longer eligible for Marsden Fund grants, the country's flagship “blue skies” funder.

Earlier this year in the United States, the National Endowment for the Humanities was gutted, with more than a thousand grants and research projects disrupted. Some funding has since been restored for next year.

In the United Kingdom, the Arts and Humanities Research Council will, from 2026, fund only a handful of projects per institution, effectively cutting off the pipeline for early-career researchers. Significant cuts to research budgets in the Netherlands and Switzerland are also impacting AHSS research.

These are not isolated missteps. They reflect a worldview in which valued knowledge is reduced to what can be patented, commercialised or measured in productivity terms. In this frame, science, technology, engineering, maths and medicine (STEMM) research equals economic competitiveness, while AHSS is dismissed as optional or a nice-to-have at best and ornamental at worst. The effect is corrosive; entire disciplines have become precarious, research autonomy is being undermined and scholars working on culture, ethics, governance or Indigenous knowledge are being left stranded.

The very fields that equip societies to question power, debate meaning and manage pluralism are the ones being hollowed out.

Meanwhile, Asia is taking a more balanced approach. China has dramatically expanded investment in history, philosophy, cultural studies and social sciences, complementing its technological strength. Singapore and South Korea are integrating the humanities with AI and biotechnology research, ensuring that ethical and cultural frameworks evolve alongside technological advances.

India is scaling up its support for the social sciences to strengthen its democracy and enhance its global role. Across the region, AHSS is not seen as an indulgence but as strategic infrastructure that is essential to nation-building, soft power and global influence.

In the West, AHSS risks being reduced to a thin margin of activity, carried on by underfunded scholars at the edges of STEMM-dominated systems. In Asia, AHSS is being deliberately nurtured as part of a holistic research ecosystem. The capacity to tell stories, frame history, interpret culture and interrogate technology will increasingly lie with those societies that invested in these fields, not with those that abandoned them.

The lesson is clear: this is not just a budget line to be trimmed. It is a choice about whether to sustain the disciplines that allow societies and humans to understand themselves and to shape their futures. If Western decisionmakers continue down the path of retrenchment, they will leave their countries with the technical capacity to build technologies, but without the cultural and ethical capability to guide their use. Democracies will weaken their own foundations of social cohesion by neglecting the very research traditions that support civic trust, cultural identity and critical debate.

The call to action is urgent: How should we live our lives?

University leaders must warn decisionmakers that cuts to AHSS research are not fiscal prudence but an act of cultural disarmament. The impacts are rapidly arriving at their front doors: polarisation, threats to democracy and law and loss of identity. We, in our institutions, must consider more deeply what others need from us. Without understanding ourselves and protecting the fundamentals of our communities, what is the value of technological gains?

The question is not whether society can afford to fund AHSS. It is whether society can afford not to. Some parts of the globe, including Asia, have already decided they cannot. The West must wake up before the loss becomes irreversible.