Why do countries keep writing international education strategies, and what do they really change?

QS Midweek Brief - February 12, 2026. What's the purpose of international education strategies? Also, discover the latest trends in the inaugural QS Sub-Saharan Africa Rankings.

Welcome! Last month, the UK released its latest international education strategy, following ones in 2013 and 2019, which itself had a 2021 update. The UK, of course, isn’t alone in having a strategy; they appear on almost every continent (no news yet of an Antarctic International Education Strategy, but we’ll cover it when it happens), and in many case, like the UK, are in their second or third iterations.

Given their popularity, we never really ask why we have them. They’re necessary, but how? This month, in a new QS Insights, we ask that very question to discover that their power is in strategically unifying a national sector.

We also include analysis of the newly launched QS World University Rankings: Sub-Saharan Africa to learn a little more about why the region’s higher ed sector is so special.

Stay insightful,

Anton John Crace

Editor in Chief, QS Insights Magazine

QS Quacquarelli Symonds

QS Sub-Saharan African Rankings 2026

By Wesley da Silva Siqueira

The regional rankings offer a unique perspective, designed to provide a more in-depth view of institutional performance within different parts of the world. After shining the spotlight on top institutions from Europe, Asia, Latin America & the Caribbean, and the Arab Region, we are proudly launching the much anticipated QS World University Rankings: Sub-Saharan Africa.

With more universities from this region represented than in the QS World University Rankings, this ranking covers institutions from almost 50 eligible countries across Eastern, Western, Southern and Middle Africa as per the United Nations geoscheme.

This means that institutions based in Northern Africa are not included in this list . Northern African institutions, however, are already covered by the QS Arab Region Rankings, based on the criteria of League of Arab States membership. The only exceptions are the institutions from Djibouti and Mauritania, which currently feature in both rankings.

The context

International student flows to Africa are still relatively small, but there is significant student and faculty mobility within and across certain countries in the continent.

Sub-Saharan Africa has the youngest population globally, with roughly 70% under the age of 30, according to the United Nations. The share of young people aged 15–24 is projected to increase substantially, rising from 19% in 2019 to an estimated 42% by 2030.

Participation in tertiary education in the region remains limited, at around 9–10%, well below the global average of approximately 42%, highlighting a large gap between demand and access, according to the 2024 UNESCO Forum on Higher Education in Africa.

Higher education systems across the region are pressured by these and other developing scenarios. The QS Sub-Saharan Africa Region Rankings is grounded in the unique characteristics, priorities and challenges of the region, allowing institutions and students to make direct comparisons among regional peers with a more granular approach to metrics.

Rankings can help institutions evaluate their performance, benchmark against peers, and identify areas where investment or strategic focus can have the greatest impact. When used thoughtfully, they function as a data-informed decision-making tool at both institutional and system levels.

This ranking brings African higher education to the forefront of policy discussion, demonstrating its role in driving economic development and a more sustainable future, while supporting regional goals such as the Association of African Universities 2030 Strategic Plan and the African Union’s Agenda 2063: The Africa We Want.

Methodology

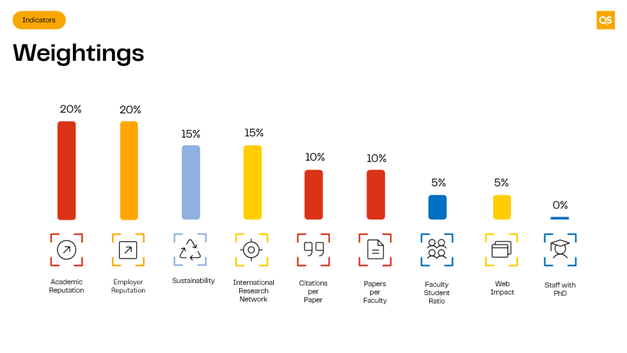

The QS World University Rankings: Sub-Saharan Africa uses indicators previously applied to other rankings, however, selected and adjusted to the measures regional stakeholders have identified as relevant.

During the process of developing its methodology, we collected feedback about which indicators should be included in this ranking from Sub-Saharan Africa-based leaders, scholars, experts, governments, and higher education institutions.

Compared to the QS World University Rankings, we use both Citations per Paper and Papers per Faculty instead of just Citations per Faculty. This allows us to compare both the impact and the volume of research being done.

We also use Staff with PhD and Webometrics Web Impact which are useful differentiating factors at a regional level. Finally, our reputation indicators here are balanced at 20% each, while International Research Network and Sustainability are weighted higher to reflect the importance of cross border research partnerships and sustainability metrics in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Results

The first edition of the QS World University Rankings: Sub-Saharan Africa lists 69 institutions out of 260 that were initially analysed. Here it is important to emphasise that not all higher education institutions are eligible for our rankings, and not all eligible institutions are ranked.

One of the main challenges in the process of gathering data for this ranking was the absence of available faculty or student data, which made it difficult to evaluate where these institutions stand compared to their peers.

However, the 69 ranked institutions already represent a very interesting jump in regional representation compared to the 19 institutions featured in the 2026 QS World University Rankings. This is even more special when it comes to newcomers, in which we see 34 institutions debuting in the QS Rankings ecosystem.

Among the 21 represented locations in the QS Sub-Saharan Africa Region Rankings, 10 of them are also featured for the first time in a QS universities publication, enjoying the visibility and momentum brought by their respective institutions.

These new institutions now enter in the roadmap to the QS World University Rankings, since one of its key inclusion criteria is for one institution to be ranked in its respective regional ranking – something not applied yet for Sub-Saharan Africa-based universities.

More than that, the regional debutants now have new engagement opportunities with local and external partners, while supporting the development of greater insights and knowledge about African higher education.

The top 20 includes prestigious universities such as the University of Cape Town, the University of Ghana, the University of Ibadan, Addis Ababa University, Makerere University and the University of Nairobi, among others.

The presence of institutions from six different locations in the top 20 reinforces an important message: strong performance is achievable across different systems and contexts. Excellence is not confined to a single national model, nor expressed in only one way.

In this sense, while South Africa is the most represented location with 14 institutions ranked, it is closely followed by Nigeria, Ethiopia, Ghana, and Kenya, with 11, 8, 7, and 6 institutions, respectively. It is a much more balanced picture when compared to other QS university rankings, where usually the top two-three countries lead in representation isolated from the other locations.

Additionally, Eastern Africa is the most represented sub-region, with 25 ranked institutions, of which 15 are debuts. It is followed by Western Africa, with 23 institutions in the ranking.

Lenses and indicators

Looking beyond overall rank, the lens-based results reveal different institutional and national strengths, reinforcing that success is not tied to one national or institutional model. Let’s look at the Research & Discovery Lens, perhaps the most insightful one in this ranking.

Nigeria and South Africa perform strongly across key research lenses, including Academic Reputation, Citations per Paper and Papers per Faculty, reflecting established research influence and productivity.

Ghana and Kenya also deliver competitive results within the Research & Discovery Lens, with institutions demonstrating strong citation impact and solid research output.

While Citations Per Paper is typically the strongest indicator, with institutions registering an average score of 39, Papers Per Faculty is typically the weakest indicator, with institutions registering an average score of 18.5. This points to a research model where institutions publish less but, when they do, their work is relatively impactful.

If we include in this analysis Academic Reputation, which also aggregates a relatively low average score of 20.4, the results suggest that visibility and legacy are standing out more than research volume in shaping perceived excellence in the region.

Finally, by looking at the highest average score by location, it’s interesting how different countries take the lead across the three Research & Discovery indicators: Uganda leads on Academic Reputation, Zambia on Citations Per Paper, South Africa on Papers per Faculty.

These patterns indicate that meaningful research strengths are present across several systems, though expressed differently from country to country.

The findings of the first edition of the QS World University Rankings: Sub-Saharan Africa, hence, highlight to local institutions and governments the importance of actively communicating research strengths and results, and not relying on legacy recognition alone.

Finally, inclusion in the rankings reflects data availability as much as performance, which underscores how for many Sub-Saharan universities, lack of visibility - not underperformance - is one of the main barriers to global recognition.

Wesley Siqueira is a specialist in strategies and policies for promoting countries as study destinations, especially across the EHEA. He also has extensive practical experience with international student recruitment activities and events. At QS, his main scope is contextualizing the QS World University Rankings results with global higher education policies and trends.

Strategic unity

By Anton John Crace

In brief:

- National international education strategies unify sectors and signal strong government backing in a competitive global market.

- These frameworks serve three key audiences, government, the sector, and the public, facilitating major cross-border successes like the establishment of new UK university campuses in India.

- Success requires managing political pressures and external shocks. While often compromises, these strategies provide essential platforms for innovation and responding to changing global conditions.

The UK international education sector has already had a strong start to the year.

In mid-January, it received what it had been anticipating for some time. After two years of policy changes and plans – such as the tightening of dependent visa rules, a planned reduction in the graduate visa’s duration from next year, an immigration white paper, and an international student levy, also planned for a later date – the government released its 2026 UK International Education Strategy.

Responses have varied.

Jamie Arrowsmith, Director of Universities UK International, called the document “an important moment” and welcomed the “renewed commitment to fostering the global reach, reputation and impact of [UK] universities” in a post on his organisation’s website.

QS Quacquarelli Symonds CEO, Jessica Turner, in a statement on her company’s website, applauded the strategy’s goals as “ambitions that matter deeply to the sector”, adding that “the strategy’s renewed emphasis on openness and reputation is therefore not only welcome, but also essential”.

Others were less generous. In a — somewhat — tongue-in-cheek response, Director of the Higher Education Policy Institute, Nick Hillman, expressed relief the strategy was “finally out”, before making a point to observe the document’s higher volume of padding, larger font size, and lack of clear “Actions” compared to its 2019 edition. In case anyone wondered if he was being sincere in those observations, he removed any doubt.

“A confident country keen to expand its share of a particular global market tends to project itself as such, whereas a thinner paper that hedges its bets may be regarded, perhaps accurately, as reflecting lukewarm support for educational exports in parts of Whitehall,” he wrote.

Hillman’s comments hint at the power of an international education strategy. For documents that can be fewer than 20 pages or, as he observes, be padded with larger-than-expected font, they can elicit strong and immediate responses.

Strategies are also clearly something that markets and governments want. In addition to the UK, Germany, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and Japan, among many others, share in having some variation of a strategy, each with their own overlapping and unique goals and ambitions.

But with so many international education strategies around the world, some recently renewed and in their infancy, reaching maturation or under review, one question doesn’t seem to be asked.

Why do we have them?

United front

One of the most obvious and significant reasons for a top-level international education strategy is that it provides a set of unifying ambitions and goals for a country’s sector. Where previously a single institution may have acted in a way to serve its own ends, a strategy creates a sense of direction for everybody. National competition becomes friendlier, or at least gets competitors in the same room, talking to each other.

But there are other benefits for an overarching document. “It's a signal of a government commitment, which means it brings government backing,” says Dr Janet Ilieva, Founder and Director of Education Insight, echoing Hillman’s observations. “It gives much greater weight for universities to be taken seriously.”

That weight leads to two things; renewed confidence for those it seeks to support, and reassurance to those it seeks to engage. This becomes doubly significant if both countries involved have complementary strategies. When UK Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer took a 125 member strong delegation to India in October 2025, for example, 14 of its members came from universities.

While not as explicitly outlined as it would become in 2026, transnational education has been a part of all of the UK’s international education strategies since their inception. India’s National Education Policy 2020, meanwhile, underscores a desire to engage with foreign universities in ways previously not allowed: namely, setting up campuses without the need for partnering with a domestic institution.

Shortly after the delegation, PM Starmer and Indian PM Narendra Modi announced that the University of Lancaster and the University of Surrey had both been approved to establish campuses in India. Effectively, one country’s national education strategy helped close the loop on another’s international education strategy.

Phil Honeywood, CEO of the International Education Association of Australia, the country’s peak body for the sector, agrees that a strategy provides firm backing, adding that the document typically serves three audiences. “The first audience is the government itself internally to benchmark performance with its own departments,” he tells QS Insights.

“And, philosophically, [it’s] to explain to the civil servants that they employ that these are the things they want prioritised.”

The second audience is the sector, and the document should reflect a degree of consultation with stakeholders and an understanding of their pain points and concerns.

The third audience is the wider community, which Honeywood says contains its own subsets. As with the case for India-UK relations, one subset is those the strategy seeks to engage with. Included in that subset is also international students, researchers, and any other individuals a country is seeking out.

The other subset is the wider domestic community “to make them better appreciate the benefits the international education brings to [a country]'s economy and future relationships”.

“A good national strategy needs to kick all three goals.”

Parts unknown

With the overarching purpose of a strategy being to unite a sector and communicate to all stakeholders a government’s intent, they still require institutional buy-in and support.

“[Strategies] don’t deliver outcomes on their own and nor are they intended to do so. They cannot replace institutional strategies,” says Sharon Calvert, Assistant Vice Chancellor, International, Engagement & Partnerships at the University of Waikato in New Zealand.

She explains that for a strategy to be a successful, institutions and subsectors must respond and align their own strategies accordingly, but that can create challenges. “Alignment is not automatic; there will always be differing views on priorities.”

In New Zealand’s case, its number of universities is small and it can therefore be easier to create alignment compared to the private training subsector, which has more providers, or other markets with a higher number of institutions. “This gap between strategy and implementation is where complexity often sits,” says Calvert.

To overcome this, there needs to be ongoing engagement between stakeholders and the government. Continued engagement has an added bonus of maintaining a strategy’s momentum after the initial excitement wanes, Calvert tells QS Insights.

“Strategies can lose momentum when they stop being discussed or are not front of mind,” she says. “Regular check-ins, visible examples of progress and regular statements on progress can help to keep the strategy relevant and front of mind.”

As the global international education sector discovered during the COVID-19 pandemic, there are also external factors that can influence the success or failure of a strategy that are unrelated to stakeholder buy-in.

“While policy frameworks provide the foundation, progress is ultimately achieved through trusted relationships, shared accountability, and an enabling environment that supports innovation, responsiveness and delivery against the strategy’s goals,” agrees Sahinde Pala, Group General Manager, International and Sector Engagement at Education New Zealand.

Pala’s second to last support, responsiveness, is itself one of the major keys to the long-term success of a strategy that is expecedt to cover up to a decade. “While strategies set direction and intent, they cannot account for external shocks, or changing global conditions,” she says.

“Geopolitical shifts, global economic pressures, or global turbulent events such as pandemics can affect the relevance, feasibility, or pace of delivery of certain aspirations.”

These realities cannot be avoided entirely, but their effects can be mitigated through continually reviewing a strategy, says Pala. The UK did just that when it provided an update to its 2019 strategy in 2021, during the pandemic. The foreword included more than 50 references to the pandemic alone.

If you can’t have the strategy you love…

There is an argument to be made that the contemporary international education sector would not exist without government-led strategies. The UK’s 2026 international education strategy is the country’s third, after releasing predecessors in 2013 and 2019, with an update in 2021, but its roots actually date back further.

In 1999, then British PM Tony Blair issued Prime Ministers Initiative on International Students (PMI) after he noticed that many professionals and leaders he met while overseas had been educated in the UK. The PMI’s headline initiative was to increase the number of international students in the UK, but its broader impacts were momentous.

“We can kind of see how international student recruitment started to evolve as a business, and it was on the back of strategy,” says Education Insights’ Dr Ilieva.

The PMI was followed by Prime Minister’s Initiative for International Education (PMI2) in 2006, which further expanded on the original initiative, and worked as a proxy strategy through to 2011.

If history doesn’t repeat, it certainly rhymes, and shortly after the PMI2 was released, a worldwide catastrophe occurred: the Global Financial Crisis. As the GFC soured the economic outlook, increased unemployment and inflation, and pushed many countries into recessions, sentiments towards foreigners soured, with international students conflated into those worries.

While sentiments eventually bounced back and the number of international students increased, there was a clear gap between the “end” of PMI2 in 2011 and the start of the UK’s first strategy in 2013. There’s also a clear change in intent, and UUKI’s Arrowsmith tells QS Insights that this change, from initiative to strategy, came from looking further afield.

Anton is Editor in Chief of QS Insights. He has been writing on the international higher ed sector for over a decade. His recognitions include the Universities Australia Higher Education Journalist of the Year at the National Press Club of Australia, and the International Education Association of Australia award for Excellence in Professional Commentary.